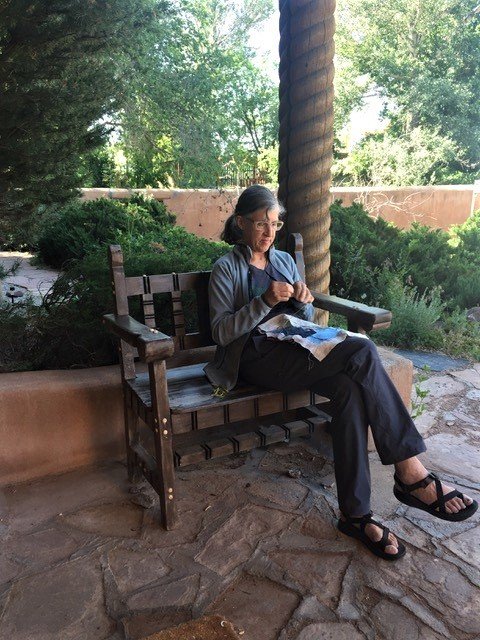

Bettina Matzkuhn takes us on a journey through her experiences with and views on craft as well as what apects have shaped her own identity as a craftsperson.

These days, when filling out forms, we are asked to identify ourselves within various categories. I don’t identify strongly with my ethnic heritage -German. I speak the language poorly and have long resented the baggage of what that country did in the years during and before WWII. I don’t identify with a religious strain. My Dad said, “Wanna talk to God? Go outside.” That suits me. Politically, I’m a tree-hugging pinko who is conservative with money. I suppose “senior” fits, but I only remember that when my back hurts or I pay bus fare. I do identify as a craftsperson.

My father was a tradesman, a perfectionist. My mother sewed, knitted, mended and wove on a loom she made for herself. They respected good materials and worked with care. Things bought were of good quality and looked after. I learned to knit and sew from Mom and spent four years building a boat with Dad. At the time, I didn’t philosophize about any of this, but I remember liking the feel of different materials, the smell of teak sawdust or the waffle pattern in a sweater. I liked seeing something tangible take shape.

In 1978-79 I worked as the summer student for Circle Craft Co-op, helping run the shop. I admired (and still do) the work I saw there, from humble mugs to impressive furniture. I remember the excitement of unpacking new ceramic work by Gordon Hutchens, lyrical glass from Brian Baxter, Barbara Heller’s tapestries that evoked layers of imagery long before photoshop. There was pain when the selection committee rejected a new member’s submission and elation if we sold something significant. I could see that craftspeople were on a spectrum of skill, opportunity, and vision. I could see an ongoing, determined search in learning and experimenting.

I worked with embroidery and fabric for years, through and after a two-year college art program. I made animated films for the NFB using textiles –a concentrated material learning curve, trying to tell stories with bits of thread. I went to university at 40, mainly to become a better writer and to try to figure out where I fit in the visual arts (still working on that). I used craft practices in my projects.

“If I embellish thrashed backpacks with embroidered paths, streams, and flowers, they might tell you something about the backpack, about a particular place, about me. Decoration carries cultural information..“

Art may employ craft materials, or even craft objects, as raw stuff or as signifiers that serve the concept. It borrows or appropriates them entirely (with varying degrees of respect). I remember feeling sorry for Robert Rauschenberg, making his painting on an old quilt to “merge art and life”. Poor sod, he didn’t realize that the quilt had already done that. The woman (most likely) who made that quilt was in dialogue with the pattern, with the colours she had available and what she thought looked good, the thickness of thread, the length of stitches and the length of minutes she found to work. Then the quilt went on to a life with one or many people, who were intimately connected to the materials and her labour. As a craft object, it didn’t have to merge art and life; it was art, and it had a life –which Rauschenberg devalued.

Some cultures value textiles but in North America, they are often dismissed as decorative. Fine. A Palestinian woman’s wedding dress will have different motifs than a North American confection. A table runner in Norway will have different patterns than a cloth in Bali. While I don’t always understand the meanings behind the decoration, I can sense it as a statement, a voicing. If I embellish thrashed backpacks with embroidered paths, streams, and flowers, they might tell you something about the backpack, about a particular place, about me. Decoration carries cultural information.

Craft, to me, is about valuing a material language and heritage. Since I grew up in the language of fibre, I can launch a compelling conversation (I hope) in that tongue. In clay or glass, I am utterly mute. In wood, I can come up with a stick figure. Trying to be articulate is the project. Some craft objects talk in the vernacular, the “hey, how’s it going”. I love them. Others whisper, some leave me speechless.

Studying art at university, we were often encouraged to quote canonical artists. This was mainly to critique, subvert or even ridicule their work. I never felt compelled to do this. In a craft practice, it is permitted to like, even cherish, one’s creative forebears. I feel gratitude to the embroiderers of history, even though I may not work in the same way. I feel a sense of evolution rather than rupture and newness. Tradition, in craft, adapts to new materials and tools and contexts. I may use the same few stitches that embroiderers used to embellish the robes of Asian or European nobility, but I use those traditional gestures to talk about climate change, or work on printed textiles of my own digital drawings. It is where I find comfort and joy, not limitation.

I’ve used embroidery and scraps of fabric to talk about my mother’s family during WWII. I’ve sewn bombs and skeletal buildings. More recently: an SUV in a swimming pool, a supertanker and smart car, a shore crab, a bleeding glacier, a hemisphere full of isobars and weather symbols, clumps of lichen. I’ve embroidered esoteric maps and diagrams. I’ve sewn a train, a hot air balloon, and a dolphin onto new dresses I made my daughter each summer. The language of fibre lets me speak to a wide audience.

” I may use the same few stitches that embroiderers used to embellish the robes of Asian or European nobility, but I use those traditional gestures to talk about climate change, or work on printed textiles of my own digital drawings.“

I identify with the metalsmiths, the ceramicists, the wood magicians, the nimble glassblowers. Their work lives with me. I have no skills like theirs, but our quests are similar. How can I tell you something with this material? How can I get you to listen more closely? How can I surprise you? I’m a hermit, my work is not. It wants to talk to you.