Bettina Matzkuhn explores what is takes for Katherine Russell to work in glass as a young mother in the back country.

The best part of living in the backcountry, says glass blower Katherine Russell, is being surrounded by mountains. There is no commute to go skiing, mountain biking or hiking. She loves coming out of her studio in the late afternoon to the light in the trees and a fresh breeze.

Russell received her BFA at the Alberta University of the Arts and worked as an assistant at a glass studio in Australia, opting to settle with her family in Elkford, a town of 2500 people in the BC side of the Rocky Mountains. With the joys of rural life come specific challenges for her practice. Russell points out that one must be organized and prepared for events like snowstorms and power outages. It’s of no use having the grant application ready to go half an hour before the deadline if the power lines are down. Similarly, when buying supplies, she makes her list and checks it twice as it is not possible to find the missing article in a small town. Getting professional photos of her work involves a journey and crating the work.

“… she needs to be organized from both a maternal and creative angle, packing human needs and all her studio glass tools & supplies.“

Blowing glass requires a significant and specific range of equipment, so once a month she drives 3.5 hours to Calgary –the closest studio to her geographically– booking time and assistance (it is not a solo activity) well ahead. She travels with one of her three sons and the other two stay home with their father. Family and friends in Calgary provide childcare as a glass studio is too full of dangers for an inquisitive small person. Russell loads the car with supplies including the cumbersome “block bucket”, a large container of water that holds wooden blocks. They need to be kept soaked, ready for their role in the glass forming process. Her son’s car seat fits over the bucket which can be another kind of adventure when his snacks fall into it. Again, she needs to be organized from both a maternal and creative angle, packing human needs and all her studio glass tools and supplies.

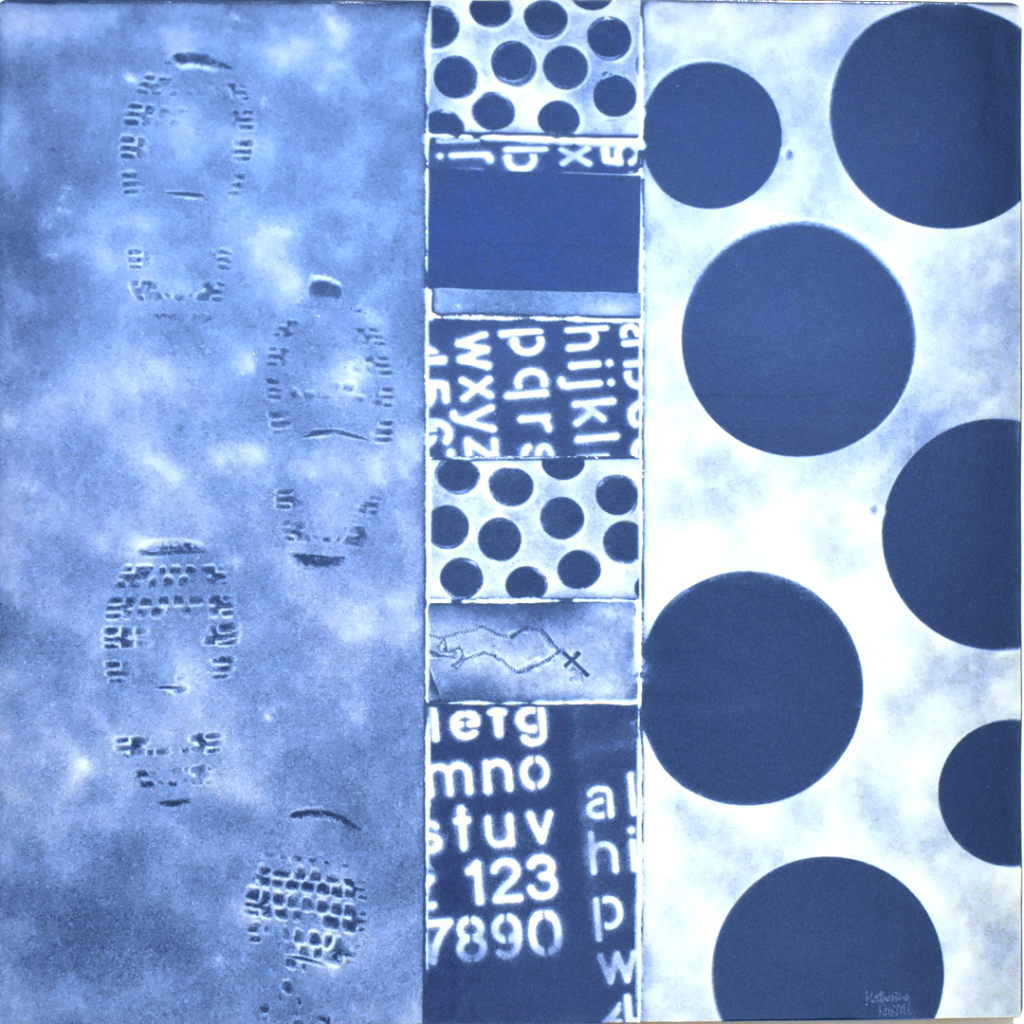

At home, Russell has a kiln-forming and cold-working studio where she can do vitrigraph work, glass fusing and slumping, sandcarving, grinding and polishing works. On occasion her shop is tidied for a studio sale event. She teaches, running full day art camps for up to eight children. They paint, draw, do glass etching and have plenty of time and room to go outside to sketch. Adults are lobbying for her to hold camps for them, too.

Sometimes she wishes that the glass blowing facilities were closer. Working there only once a month does not allow her to be spontaneous if a great idea presents itself. It also feels to her as if the first day in the studio is a coming-up-to-speed day, revisiting the physical and logistical dance of the work. Her stint in the studio is a valued time to be with her creative community, to talk shop and brainstorm, to get a useful critical response. While other creative people live in her town, they are not invested in this demanding medium.

Russell tries to make time to experiment. She plays with new colour combinations and processes with what is available to her at home. Between the rigorous scheduling, restocking, filling orders and unsexy but necessary administrative work involved in creative life, she has made the constraints of home and away manageable. Especially when the studio door opens at the end of the day to some mountain splendour.

Bettina Matzkuhn