In conjunction with her CCBC gallery show, we asked artist Bettina Matzkuhn to share with us a bit about her creative progress and her relationship with drawing.

The exhibition will be on view in our gallery from October 6 – November 24, 2022.

Drawing is essential to my working process. It allows me to notice, to consider, to inspect. It’s fun: doodling and imagining. I use it to record and to plan. My practice consists mainly of hand embroidery, a sedimentary progression where small stitches accumulate into textured surfaces and images. Embroidery is like drawing in that it is a form of mark-making, but slower. I keep sketchbooks handy: usually a large one I dedicate to a theme and a small one I carry around for impromptu drawings. I draw on hiking trips –quickly so as not to annoy my companions with my dawdling-doodling. It’s important to look carefully when making even a modest drawing, whereas taking a photograph can simply involve clicking the shutter. In the small books, the sketches vividly recall where I was at the time. Drawing fixes memory. The eye, the hand and the brain hum together.

” When drawing, time seems to fall away and I am immersed in the unfamiliar forms, in the hand to eye process of judging contours and relationships.“

To imagine work I am going to make, I make many drawings of the thing or view to be embroidered. I draw to map out compositional elements. I will burn embroidery before I unpick it –that takes longer than the actual sewing. I would rather invest a little planning upfront to give me a sense of what I am working towards. That said, each piece takes on a life of its own and I enjoy the surprises.

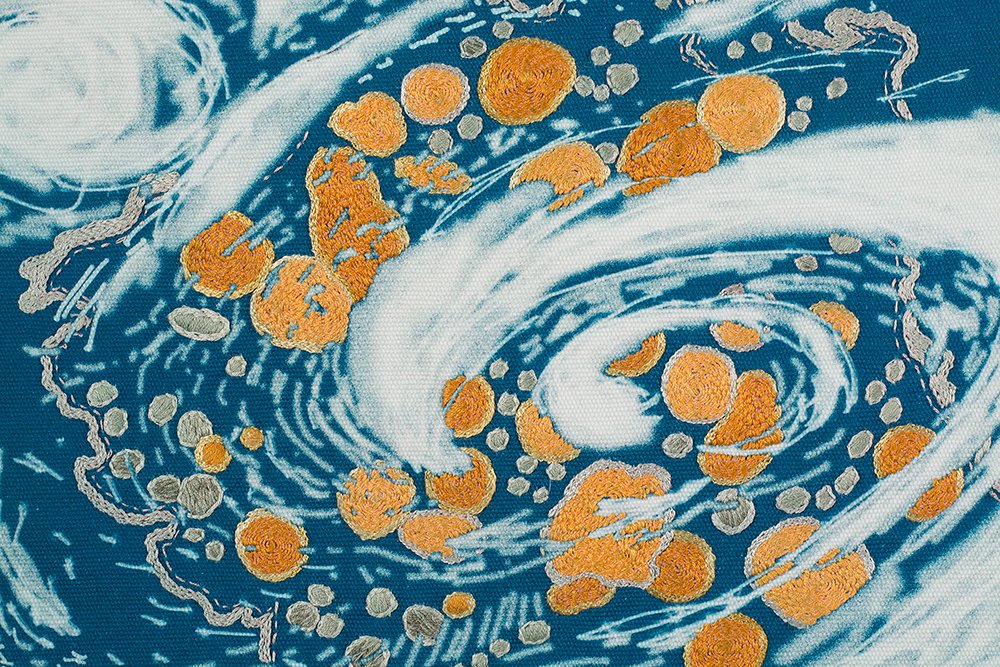

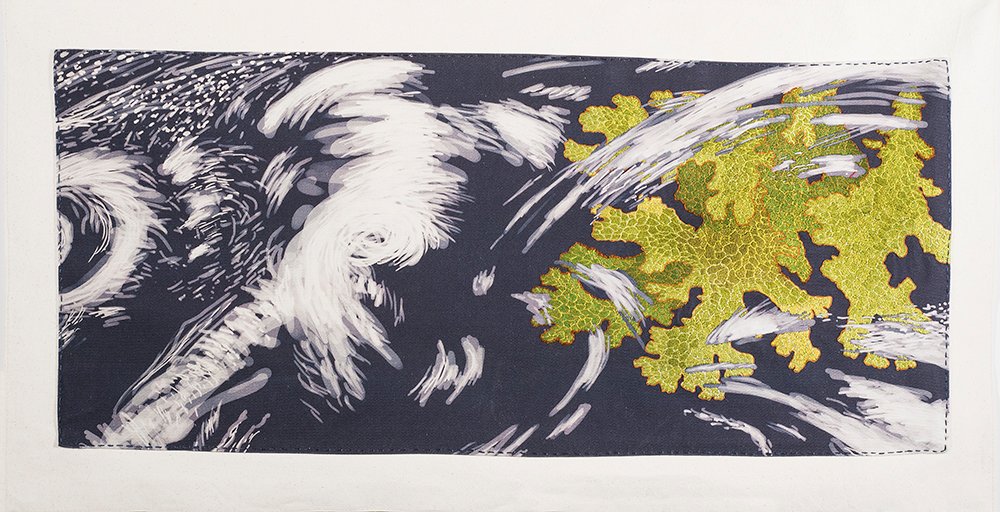

For the Meteo-Botany project (seventeen pieces at present count), I drew weather systems from a satellite feed I check daily. From this “god’s-eye” view, I could see masses of clouds trapped offshore while the fires roared across B.C., watch the atmospheric river span the Pacific Ocean to flood the Fraser Valley and, more benignly, see sudsy patterns in the wake of low-pressure spirals.

Working with Photoshop and a digital drawing pad, I can draw in layers, with light over dark, and in varying degrees of translucence. I can hide or delete elements as necessary. I have finished drawings commercially printed onto fabric. The digital drawings seemed to ask for comment. During the Covid lockdown I began to work on two drawings that had been printed onto fabric –embroidering one with alpine flora and one with kelp. I undertook them without a planned series in mind, but like most craftspeople, I think best while working on something.

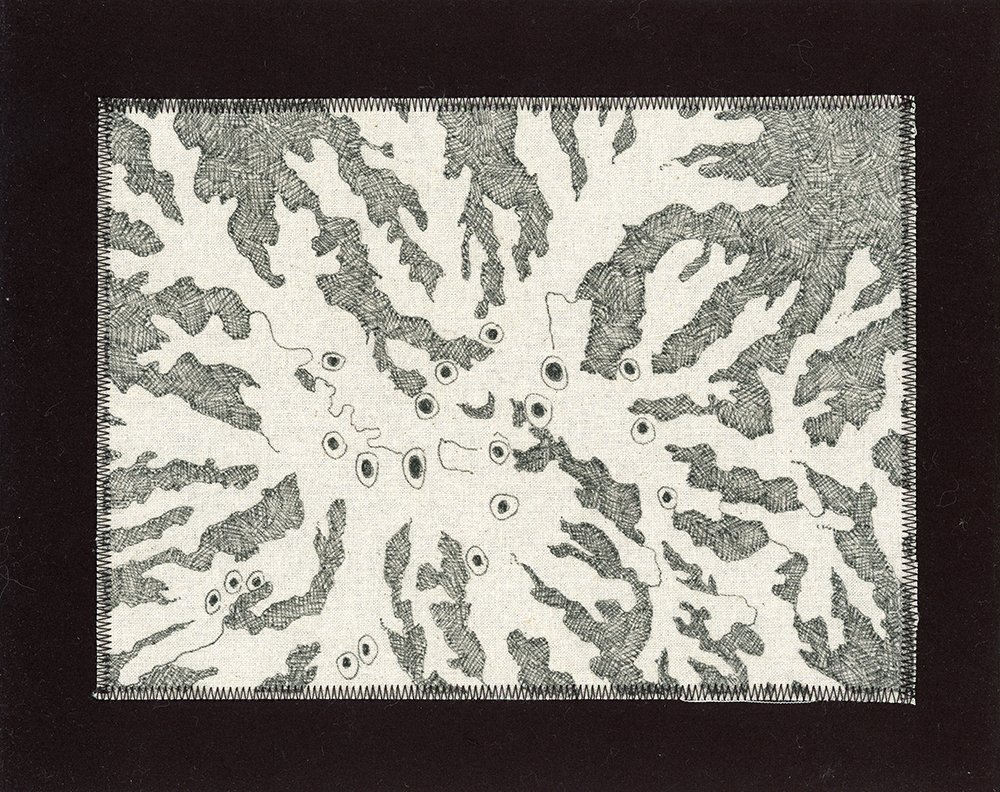

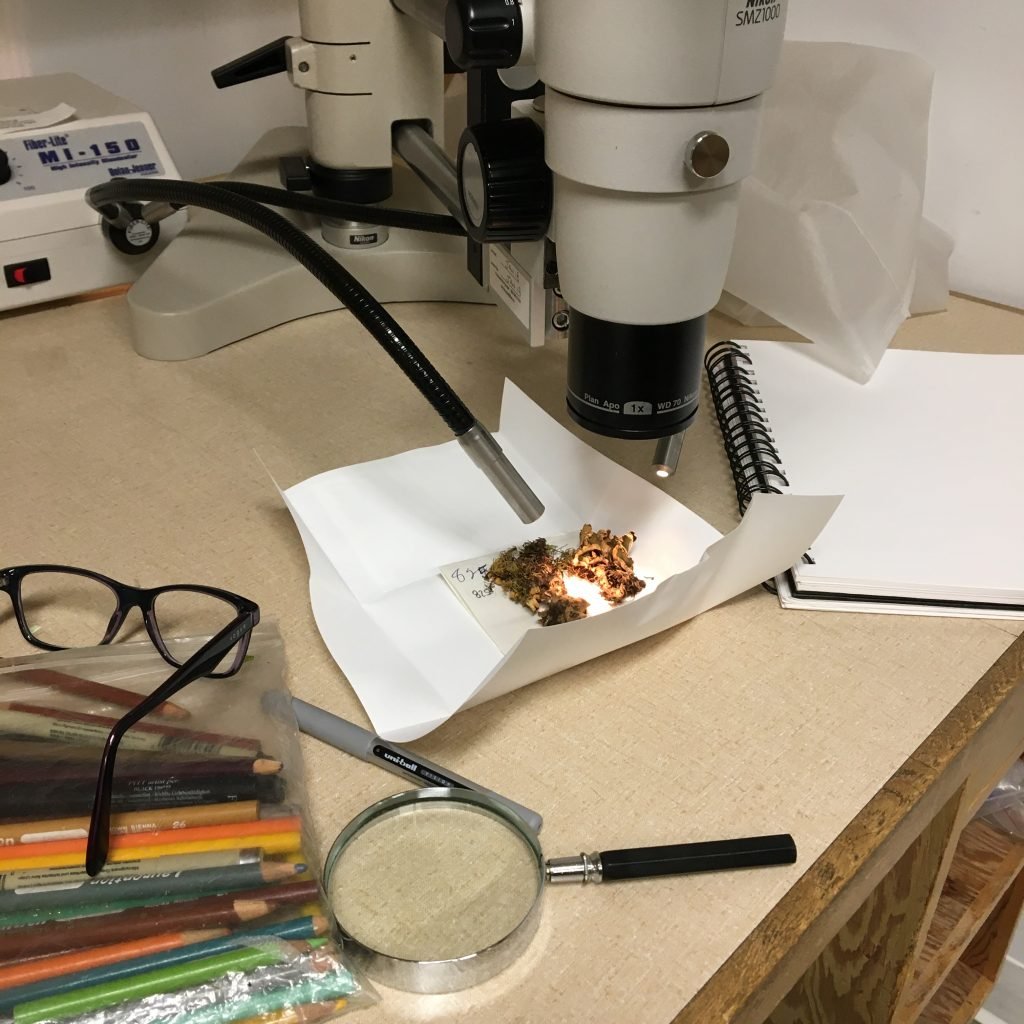

I thought about smaller life forms dwelling amongst the weather systems that have such a pervasive impact on what lies below. The contrast of scale seems important. I considered what literally lives underfoot –often out of sight yet significant to ecology: mosses, lichens, microbes, fungi, germs, and seeds. Combing through my hiking photos, I found many of lichens. Such colourful, diverse, and strange little beings, minding their business on branches and rocks in all kinds of weather. Their forms can range from what appears to be a bit of dust to extravagant leaf-like shapes. I arranged to draw lichen specimens at UBC’s Beaty Biodiversity Museum, an institution well worth the visit for anyone interested in natural history.

Parked at a microscope with small paper envelopes of specimens, a new world opened. When drawing, time seems to fall away and I am immersed in the unfamiliar forms, in the hand to eye process of judging contours and relationships. The first drawings were too small. Subsequent ones filled entire pages and were easier to translate to embroidery. Noticing begets more noticing and I often found myself stopping outdoors –in the city or farther afield– to draw or photograph lichens. Trying to identify them, as a lichenologist pointed out, is more than simply visual. It involves chemical testing to differentiate species that may look very similar yet are unrelated. I noticed that the museum specimens’ colours were sometimes faded so I referred to my photos or online images to arrive at a more representative colour when beginning the embroidery. It is a joy to be immersed in the fractal branching where noticing leads to more noticing.

All my work goes through iteration; a piece never appears fully formed in my head. Drawing plays a significant role in how something evolves. Drawing digitally –yet still by hand, using mechanical processes to print the drawing, and adding to the image again by hand has been a rewarding process. I like how the modern technological component is bookended by ancient and traditional practices.

Recombining elements to create new meanings is one tool in the artist’s repertoire, a visual experiment. Lichens are tough characters, living beings under the shifting sky. They have evolved to their locales, often co-habiting with other lichens and flora, reproducing, clinging to their homes as best they can. I hope that by meshing the grand with the miniscule, viewers might go on to imagine what else is sandwiched between the atmosphere and the ground.

Bettina Matzkuhn explores themes of ecology, weather, and landscape in her textile work. Emphasizing hand embroidery, she values the versatile language of textiles. Matzkuhn holds a BFA and an MA from Simon Fraser University, and is the recipient of Canada Council and British Columbia Arts Council Grants. She has exhibited in solo and group exhibitions across Canada, as well as in Korea and the United States.

Her work is found in national public collections such as the Surrey Art Gallery, Cambridge Art Galleries and the Weldon Map Library at Western University. She lives and works in Vancouver, British Columbia.