2022 Micki Mackenzie Awardee and ceramicist Ilana Fonariov shares her experience as she continues her practice and education journey at Selkirk School of Arts – now as she has ventured into the realm of glazes. You can read Ilana’s previous article here.

FLUX – the latest word in my pottery ponders, and one that is relevant to my schooling in both a literal and figurative sense. In the world of glazes, flux is a category for materials that generally have lower melting points. Their addition to a glaze is what allows it to be fired to maturity at temperatures accessible to most potters.

What do fluxes have to do with my practice?

“As someone who doesn’t actually enjoy glazing, the idea of having a flame do my work for me was very appealing.“

In a literal sense, I’ve been learning to work with wood ash, which can function as a flux. The idea to explore wood ash surfaced after a lecture on wood firing, where I saw images of pots glazed by flames. That is, ash from the fire’s flames was deposited onto the pots and then melted into glazes on those same pots. As someone who doesn’t actually enjoy glazing, the idea of having a flame do my glaze work for me was very appealing. Plus, the visual effects were satisfying.

Unfortunately, I don’t have access to a wood kiln at home, and I lack the expertise and experience in this very labour-intensive and highly skilled art form to put those flames to work in the near future. Nevertheless, the concept of wood ash and glazes set my brain ablaze. I had always thought the idea of wood ash glazes was too fantastical and too out of reach – how could it be possible to make a glaze out of something so coarse, something so unlike glass?

It comes down to one of the basic principles of chemistry: all matter melts, irrespective of its appearance.

Wood ash starts melting at around 1200 degrees Celsius, or cone 6, which is what I usually fire to. If I were to fire at a higher temperature, I could probably just mix wood ash and water (and clay to help suspend it), put that on a pot and call it a day. However, at cone 6, an additional fluxing agent is needed to achieve an adequate melt.

I mixed up many small batches of glazes to test different ratios and percentages of ash to clay and an additional flux. It was agonizing at times to push coarse ash through a small sieve, but I persevered because promising results came out of the kiln and disproved my assumptions of what is “too fantastical.” My motivation to make it work was and continues to be strong.

The desire to have a more sustainable business and artistic practice is what fuels me. Most pottery supply stores sell glaze materials in plastic bags; some materials are extracted in problematic ways (see: cobalt mining), and others involve impactful industrial processes. Not many are locally mined. Ash doesn’t come in bags and can be sourced locally, like from my wood stove, or better yet, from Galiano Island’s Charmer, which makes the best wood fired sourdough pizza I’ve ever had. Also, ash is free – at least monetarily speaking.

I quickly discovered that ash does cost a lot of time to process. I had to sieve it several different ways: with a coarse sieve to separate things like unburned charcoal, chicken bones and whatever else might have been thrown into the wood stove (this was not the case from Charmer’s ash, as it turned out to be the cleanest ash I had come across); a finer sieve for materials like small rocks; and then sieve twice more when mixed with the rest of the glaze ingredients. And I have to emphasize that ash does not go through a sieve willingly.

Eventually I also tried washing my ash. Washing ash is kind of what it sounds like: I add water to the ash, decant it daily and add new water to the mix until it stops “bubbling” when I do so. This is one way to rid it of elements that change the chemistry of the glaze over time, which would alter its application, usability and appearance.

I then dry it out in a bisque fired bowl I made specifically for this use. Once the water has evaporated, it is ready for coarse sieving and weighing for the glaze.

When I finally got a test tile out of the kiln that looked like a proper glaze, one with good movement and melt, one that would be food safe and durable, and one that resulted in lovely earth tones, I messaged my teacher:

“We made an actual glaze!!” (I say “we” because he was guiding my explorations).

He replied with confusion… Why did I doubt that it would work?

I guess it just felt too good to be true, too magical. Is there really a material I can use in my practice that would otherwise be a waste to most people, which is “free” and which also gives me the visual and functional effects that I want?

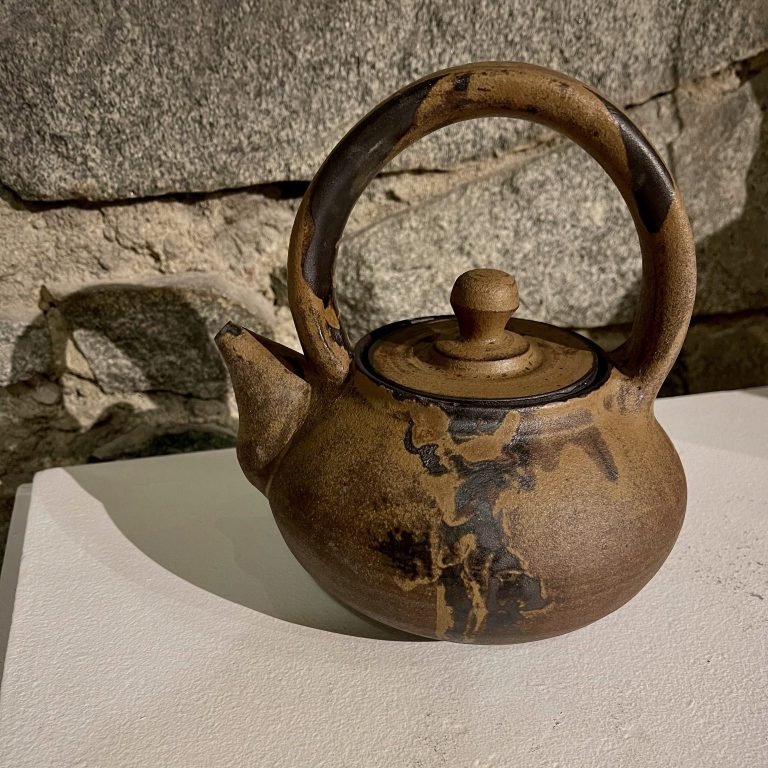

When I finally applied my new ash glaze to a mug, I was elated to see how it emulated some of the earthiness I longed for, the kind I had only seen in gas firings or with black clay! And here it was, achieved without direct use of fossil fuels. It was hard to believe.

I was more idealistic and romantic as a child. I even believed in fantasy and magic. I abandoned my romanticism and the fantastical in my teenage years because I thought such ideas only led to disappointment. But lately I’ve come to understand that my definition of magic was simply too narrow. Magic exists. It may just go by different names and manifest in various ways I didn’t recognize.

Chemistry can be one form of magic. Even though I understand some chemical reactions, they can still be fantastical if I let myself be awed. Some chemical reactions seem to defy logic (see: eutectic reactions). The alchemy that happens in a kiln amidst the fluxes and glass formers and stiffeners is truly transformational.

All of these experiments in glaze making have matured my practice; and flux, as something that catalyzes melt and maturity, seems like an appropriate metaphor for my schooling then. I am still very much in flux. And that feels like magic.

Micki MacKenzie 2022 Awardee Ilana Fonariov is a self-taught potter living and working in Galiano Island. Ilana is a lover of clay and its malleability; she is drawn to black clay most of all, for its drama and starkness and for the challenge of finding ways to soften it. With this bursary, Ilana seeks to develop her art through a ceramics program at Selkirk college in the fall of 2022.