Louise Perrone discusses the history of pin-back badges, or buttons, and her personal relationship to the communications tool that presents itself as both art object and souvenir in her exhibition Fruits of my Labour.

Fruits of my Labour is on view in our gallery until November 25, 2021.

The final piece in Fruits of my Labour that most viewers will encounter is a large white canvas covered in pin-back buttons (or badges as they are known in the UK). Tucked into the corner of the installation that I refer to in my artist statement as “The Gift Shop”, with explicit instructions not to touch, individual pins are available to purchase in the CCBC Gallery shop. They are likely to become many visitors’ most significant takeaway from the exhibition – something they will wear.

This extract from The Button Guy Blog discusses the versatility of badges as tools for communication and the dissemination of ideas: “A button is a messaging tool, a person to person communications device. A button maker is having your own printing press. You can comment on issues on a day to day basis and sit on the subway a month later and see someone wearing your message. A button is a small canvas for ordinary people to express themselves. A button can be the weapon of the oppressed or a quiet form of passive resistance.” [1]

“…a button maker is having your own printing press…“

The history of badges dates back to 1787 when Josiah Wedgwood produced a slogan stamp for wax that was later reproduced as a porcelain cameo to promote the British anti-slavery movement. To the right, you can see the US Patent taken out in 1896 by George B Adams, George for a badge pin or button.

When Queen Victoria celebrated her Diamond Jubilee in 1897, souvenir badges like the one pictured below were mass-produced and sold internationally. Since then, badges have been an effective messaging tool used in political campaigns, advertising, and popular culture, and have become the subject of many collections, including my own

I started collecting badges in my pre-teens, buying them on school trips to museums, picking them up for free at various local businesses, and pinning them to a cushion. My hobby is not unusual – the compulsion to build a collection of everyday items has been practiced by humans for thousands of years and is often attributed to an emotional connection to particular objects. However, a 2014 study turned this idea on its head. In “The Influence of Initial Possession Level on Consumers’ Adoption of a Collection Goal: A Tipping Point Effect,” Leilei Gao, Yanliu Huang, and Itamar Simonson propose that starting a collection is likely triggered by our discomfort with owning an unstable, small number of possessions and our desire to justify what we have by amassing more of the same, creating meaning from meaningless objects, each new acquisition validating the last.

The careful display of badges pinned by hand to an artist’s canvas in Fruits Of My Labour seeks to satisfy this need, repeating the image of the banana over and over again, questioning the message that more is better.

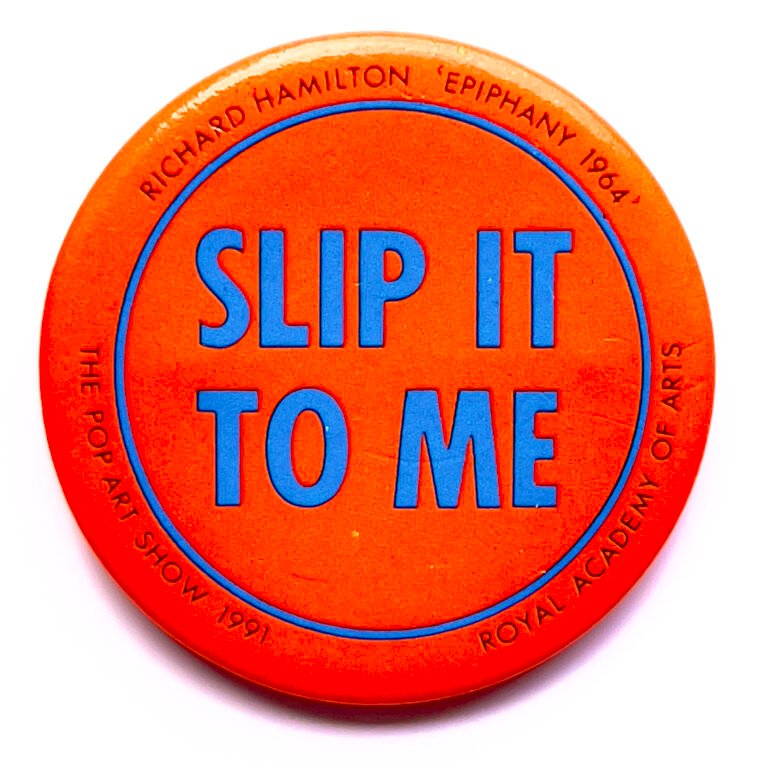

Mass consumption and popular culture are themes that were explored in the 1950-1970s by the Pop art movement. Pop art has influenced my work since I visited the 1991 blockbuster exhibition “The Pop Art Show” at the Royal Academy of Arts as an art student and purchased my favorite badge of all time, pictured above. Ironically, the image on the badge is from a large painting of a badge – British artist Richard Hamilton’s 1964 “Epiphany” which depicts an orange and blue badge with the slogan “SLIP IT TO ME” that he had encountered on a trip to the USA: “Epiphany is a souvenir of America…On my return it stood for much of what I had enjoyed in experiencing the States but it also summed up that which I most admired in American art, its audacity and wit.” (R. Hamilton, quoted in Richard Hamilton: Paintings etc’. 56-64, exh. cat., London, 1964, unpaged)

Like the Royal Academy of Art’s Pop Art Show badge, the badges in Fruits Of My Labour depict an object from the exhibition, the hand-sewn magenta Banana Split Necklace that appears as a sculptural object, a framed print of a model wearing the necklace, and a postcard in the gift shop. The badges were made to function as both part of the exhibition and as souvenirs for the show, an attempt to democratize the experience of entering an environment that sells artist-made, one-of-a-kind, and limited-edition craft objects, questioning the value of labour in a culture of mass consumption.

Follow Louise