Amanda Wood writes about how her willingness to let the material lead gave her a deeper understanding of the materials fundamental to her practice. She dives into the philosophical underpinnings behind INTERWOVEN and presents a fresh way of viewing material, not as something manipulated by human imposition but as something independent and forceful. Amanda’s exhibition INTERWOVEN is on view in our gallery until August 19, 2021.

“It doesn’t happen all at once,” said the Skin Horse. “You become. It takes a long time. That’s why it doesn’t happen often to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don’t matter at all, because once you are Real you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand.”

The Velveteen Rabbit or How Toys Become Real

Margery Williams

The character of the Skin Horse in the children’s book The Velveteen Rabbit inhabits all the qualities of what Tim Ingold calls thingness, it is a method for working in a studio practice, and a process of letting go, as an object emerges following the natural forces and flow of materials.

… what people do with materials, as we have seen, is to follow them, weaving their own lines of becoming into the texture of material flows comprising the lifeworld. Out of this, there emerge the kinds of things we call buildings, plants, pies and paintings.

Textility of making

Tim Ingold

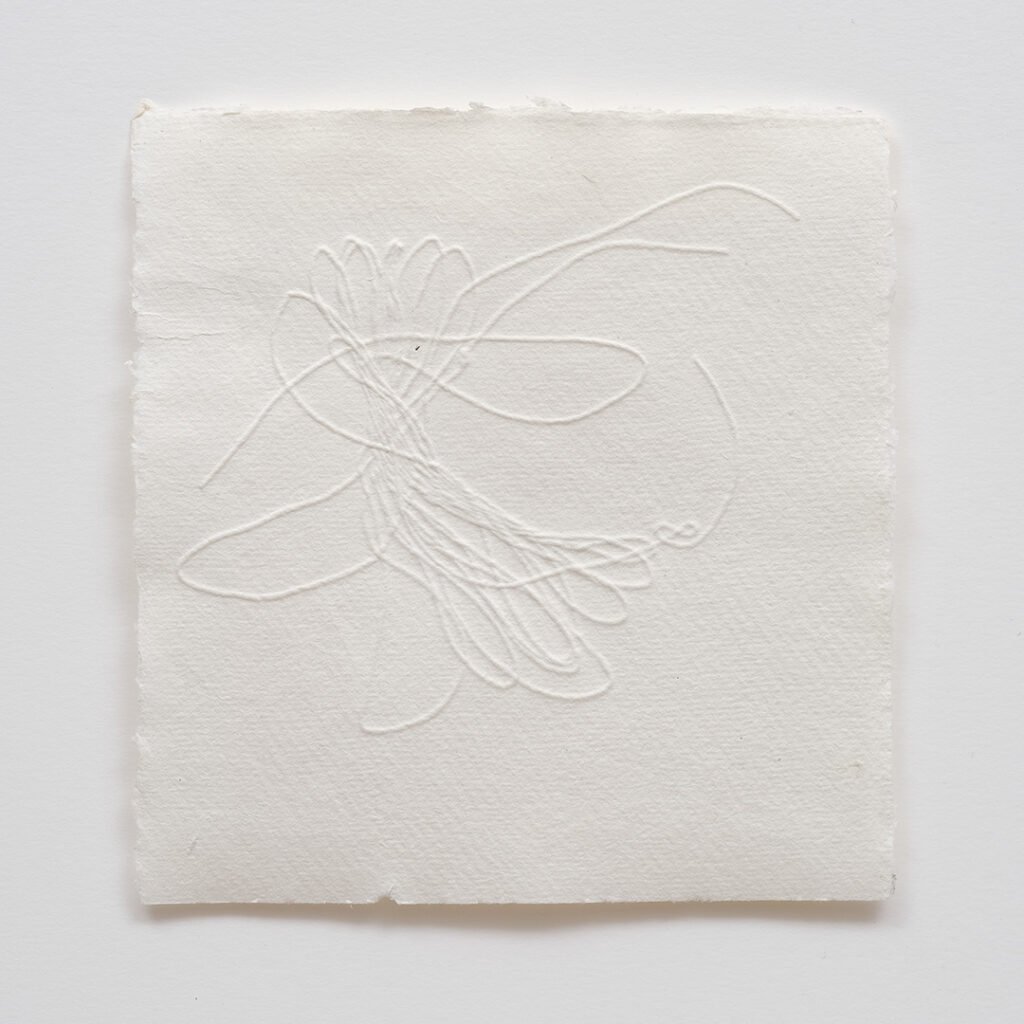

At the beginning of my self-directed residency, I was working with unfamiliar processes and materials. Taking time to experiment and listen to each material. It felt indulgent and awkward at first and I was drawn to seeking out a structure to hang it all on so I could justify the work. I wanted to find that little bit of poetry that I had seen in discarded objects. I wanted to capture the transitory forms I was seeing in a way that suggested a sense of duration.

I didn’t have a Skin Horse to consult so I looked backwards into art history, and I was reminded of a notebook page from the sculptor, Eva Hesse written in 1968 when she was working in a new medium to her – silicone. Underneath a heading of Problems in Art, she had drawn a triangle and labelled each point – content, materiality, process with the implication that the centre represented her outcome. Process was at the top and in all caps. I interpreted this to mean that process was her driving force.

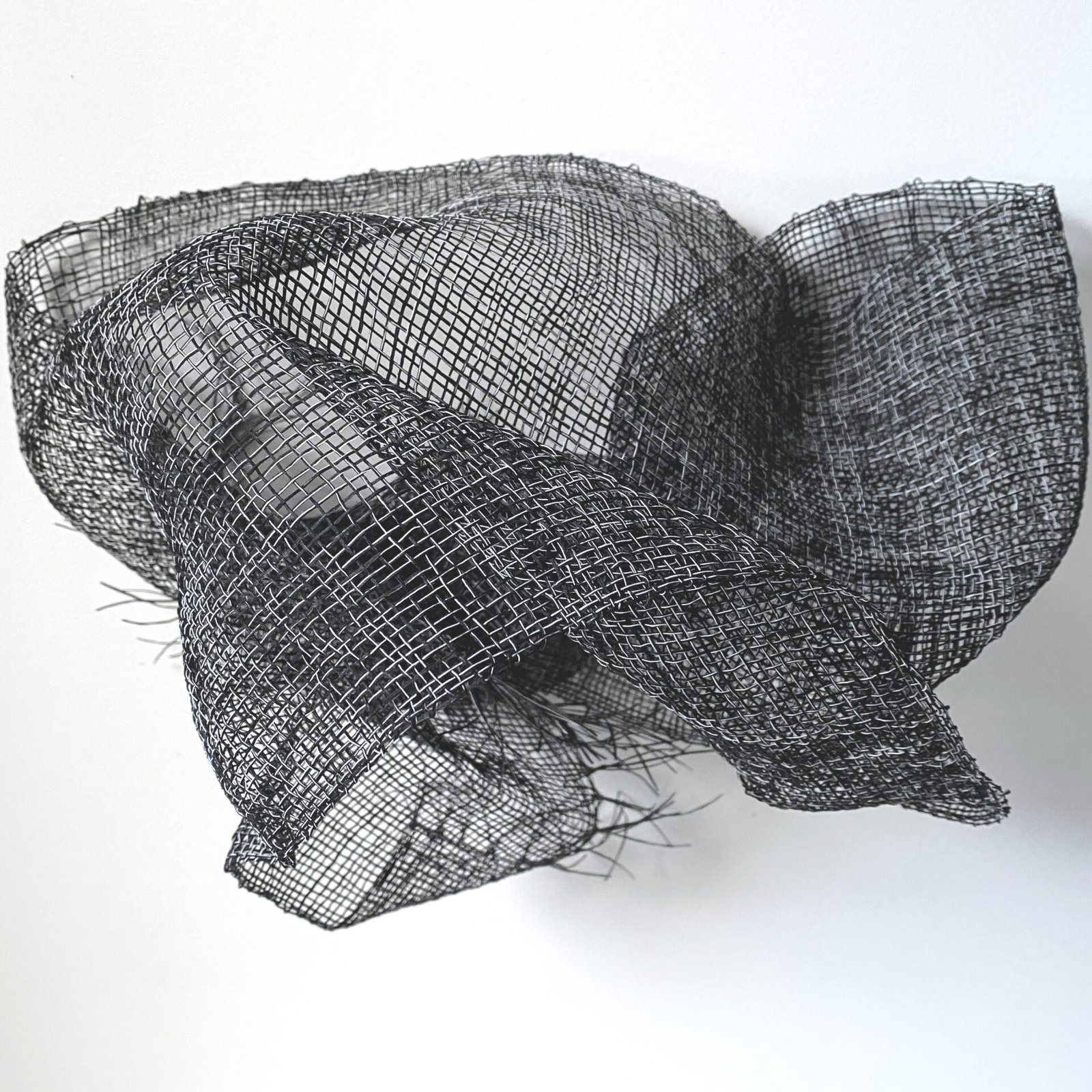

At around the same time I was introduced to object-oriented ontology, a form of philosophical questioning which tries to understand the beingness of an object without imposing human perception upon it. This way of thinking sent me down so many wonderful rabbit holes and has since become a touchstone for me in my studio practice as it allows me to re-orient myself in relation to materials. With these new processes I was able to explore what happens when forms emerge directly from the materials rather than through imposing an idea or form onto them.

“With these new processes I was able to explore what happens when forms emerge directly from the materials rather than through imposing an idea or form onto them.“

In the Textility of Making, Tim Ingold takes object-oriented ontology even further by suggesting that an object is never static. In the process of making and sharing work, the artist collaborates with the materials, a viewer is invited to engage with the resulting object all the while the object is quietly and slowly continuing to transform as the forces of time alter its material properties, just like the Skin Horse.

In the Textility of Making, Ingold writes “artists—as also artisans—are itinerant wayfarers. They make their way through the taskscape as do walkers through the landscape, bringing forth their work as they press on with their own lives. It is in this very forward movement that the creativity of the work is to be found…To improvise is to follow the ways of the world, as they open up, rather than to recover a chain of connections, from an end-point to a starting-point, on a route already travelled.”

I love the idea of working as an itinerant wayfarer meeting fellow travellers, being transformed by the experience, and learning along the way. I follow tangents, invite chance, and embrace imperfection, knowing I may glimpse something unseen if I am open to it. In INTERWOVEN I have included objects which might be considered finished and objects which might not. Objects that are process driven and follow the unique flow of the materials. I am excited to continue to play with the ambiguity and sense of freedom in the experience of making and sharing work in this way.

Further reading:

Ahmed, S. Orientations Matter. (2010). In Coole, D., & Frost, S. (ed.) New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics (pp. 234-257). Duke University Press Books.

Eva Hesse: Oberlin Drawings, Hauser and Wirth, 2019.

Ingold, T. (2009). The textility of making. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 34(1), 91–102.

Williams, M., & Berg, M. (2015). The Velveteen Rabbit: or How Toys Become Real (Illustrated ed.). Maurice Bassett.